Researching new methods of wood protection are of key importance for the work we do here at Critical Concrete. Wood is the primary material we use to build and renovate houses; from the structure, to the cladding, and the furniture. Priorities of our wood protection solutions include; relatively low-cost, accessible materials, simple recipes. Prioritising these aspects means it is easy to scale up for large projects.

Tricoil

For our renovation project in Esposende, we rebuilt the roof with a wooden structure, so it was essential to protect the wood for the longevity of the building. With the cladding substructure, window lintel, and furniture we had a lot of wood to treat. Through research of various recipes we came up with a recipe and method which fit the requirements we had.

TRICOIL (Turpentine/Tung Raw Linseed I Coconut OIL or 3 oil) is a blend of three different oils which gives protection from parasites and environmental conditions. Linseed oil, Tung oil, and Coconut oil are blended together using turpentine as a solvent to combine the oils and allow for deeper penetration of tricoil into the wood. The original recipe and method we based this upon can be found here [1].

Tung oil has been used by the Chinese for hundreds of years to protect wooden boats. It is derived from pressing the nuts of the Tung tree. It has anti-termitic properties and offers durable waterproofing.

Raw Linseed oil, obtained from pressing flax seeds, creates a water repellent barrier on the wood.

Coconut oil, rich in fatty acids, nourishes and protects the wood.

Turpentine, a solvent derived from tree resin, thins and blends the oils for easy application to the wood.

Method

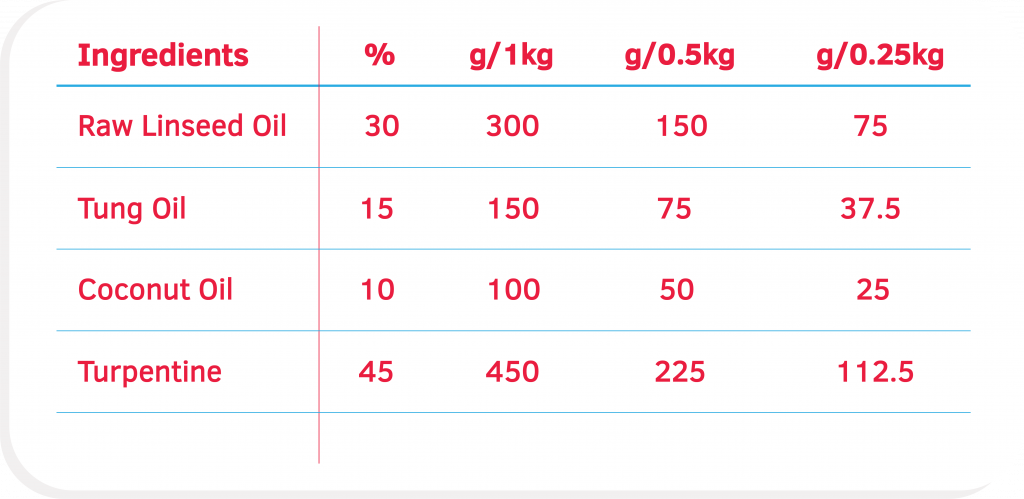

Ratio of ingredients for TRICOIL

Heat a large pot of water to 50°C to act as a bain-marie. Place a jar of coconut oil and turpentine into the bain-marie and cook until this mixture has also reached 50°C, stir often. If you have a big enough pot, you can do the same with the linseed oil and tung oil together in one jar, placed in the bain-marie. Once the mixtures have reached the temperature, mix them together.

The Tricoil is now ready to be applied on clean, sanded wood. Apply to the wood once per day for 3-4 days and dry in an open space.

Burning Station

Since discovering the wonders of Yakisugi, it has become a firm favourite as a method of protecting wood in many of our projects. Our first article in wood protection dives into the science of the method and the properties of charred wood.

After a fair few projects using our brick burning station at CC HQ, we enlisted it for charring wood for the cladding of the Esposende house. Around a half ton of bricks were put in the van and rebuilt on the street. After so many uses at such high temperatures the normal bricks and even special fire-bricks began to crack and posed a risk of collapse while using the stove. Thus we decided to design a new, super-portable, efficient charring station.

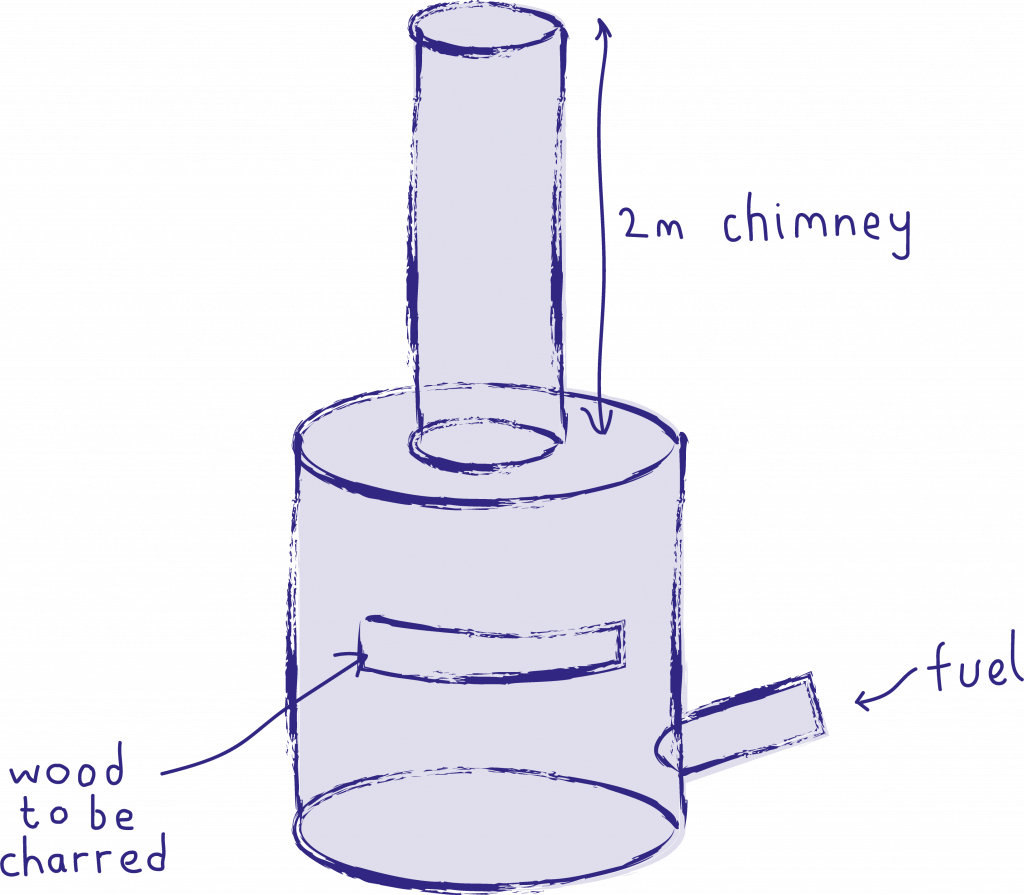

Blueprint of the new charring station

The body of the charring station consists of an old oil drum, an inlet for passing the wood to be treated through, a feeder for fuel, and a hole to attach a chimney. It mimics the previous charring station with the L shape encouraging an upward draft. The feeder is made of an old fire extinguisher welded on with extra metal for support.

With the use of two rollers, 1 person can manage the charring station themselves. If the fire is burning well and frequently stocked, it is possible to char a 3m 30x3cm board in 10-15 minutes for both sides.

The efficiency and speed of this burning station allowed us to burn all the wood for the board and batten cladding of the house in Esposende. Furthermore, this higher degree of flame control allowed us to achieve a uniform result for the boards to not warp and lose their integrity.

For improvements of the burning station we would advise a metal plate on the lip of the openings for the board to rest on – otherwise it can mark the board. Additionally, a way to adjust the opening for different sizes of boards would increase the efficiency by reducing excess draft.

Top Tips

Have an ample supply of fuel available to keep the fire well stocked and at a medium-high flame.If the flame is burning too high it is better to do a few quick passes to avoid over-charring the wood which can result in warping.Apply raw linseed oil after charring to compensate for loss of moisture and flexibility.If the wood does warp and you are using it for board and batten cladding, mount the board with the bend curving away from the wall to reduce pressure and prevent cracking.

There are a few drawbacks of this method and these should be considered before employing this technique in your own projects. One is the time intensive nature of the process. The burning station was fired up most days of the 6 weeks of Esposende workshop. This works if there are many hands available to take on the relatively low-skill task and take turns amongst each other. However it may prove tiresome for a self-build project. The second drawback is the issue of smoke. At Critical Concrete HQ we have neighbours in close proximity, requiring us to build an extra tall chimney to prevent smoking out the neighbours. Having ample space is also a factor to consider. The actual working site of Esposende was relatively small, however, we were lucky to be able to use the quiet street, much to the amusement of the neighbours! Looking to our next renovation project we will need to contain construction activities as much as possible as the street is very narrow with no pavement. For situations when these drawbacks are apparent we endeavour to find more suitable solutions.

New burning station

Yakisugi cladding on wooden substructure treated with TRICOIL

Swedish Paint / Flour Paint

Filling the requirements of cheap, scalable, non-toxic and accessible ingredients, Swedish Paint is an excellent choice. Swedish paint has long been used as the primary choice for wood protection in many Nordic countries. It can endure the harsh climate while offering an appealing aesthetic.

Swedish Paint can last for up to a decade before a new application is needed.

Photo by Anders Nord

Method

This is a new method for us and we have tried out one recipe using the materials we had available in the workshop [2].

For 3 litres of paint the following measurements can be used:

300g of flour3l of water600g of pigment300ml of linseed oil

For pigment, we used red clay that we had left over from making a rammed earth floor and wood ash from a local saw mill. There are many options for pigment, do some research and see what is available in your local area.

This is the very beginning of our research with Swedish paint so there will be more information to come in the future as we experiment with different recipes and ingredients. We will leave these samples outside to see how they withstand the weather.

Paint samples using wood ash and clay

References

[1] https://www.artamin.it/impregnante-ad-olio-fatto-in-casa/

[2] https://engelleben-free-fr.translate.goog/index.php/recette-de-la-peinture-a-la-farine-protection-des-bois-exterieurs?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=ajax,elem&_x_tr_sch=http

The post Natural Wood Protection – Vol. 2 first appeared on Critical Concrete.

Did you miss our previous article…

https://www.akbarconcreteworks.com/?p=110